Hark! A voice, the darkness choosing,

Calls my new born soul away.

Lately, launched, a trembling stranger,

On the worlds wild boisterous flood,

Pierc’d with sorrows, tossed with danger,

Gladly I return to God.

–From Lines on the Death of a Child,

By a member of the Ludlow/Frey Family

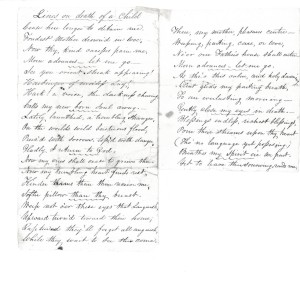

In 2014, as I completed my dissertation The Children of Spring Street: The Remains of Childhood in a Nineteenth Century Abolitionist Congregation, I selected two stanzas from a poem, Lines on the Death of a Child, to open and close the story of the children of Spring Street. This poem was written about the death of Anna Frey, a child who died in 1830. I had found the poem among the Reverend Ludlow’s papers. The Reverend Ludlow was the third pastor of the Spring Street Presbyterian Church, between 1825 and 1837. His sister, Caroline, had married into the Frey family, and so I suspected that this little girl was a relative of his, either by marriage or more directly. The poem is from the perspective of the little girl, who “Gladly” goes to heaven after a brief time in this world (the full poem is transcribed at the end of this post, below). It is unclear who wrote the poem, but it was obviously written by a member of Anna Frey’s family. And so for me, the poem became a way to introduce the idea of the importance of children to their families, and the impact of their deaths on the lives of those who loved them. Despite doing some digging, I was unable to uncover any more about Anna Frey herself. So the poem became less about a specific girl and her specific life and death, and instead became a symbol to stand in for all of the children I would study.

It was with great surprise this past week, two years later, that I encountered Anna Frey’s name again. Over the summer of 2015, Dr. Shannon Novak and graduate student Cristina Watson worked through the New York City Death Records at the Family History Library of the Church of Latter-Day Saints in Salt Lake City, Utah. They transcribed the names, addresses, birth locations, dates of death, causes of death, and other information recorded about each person listed as buried at the Spring Street Presbyterian Church. This has given those of us working on the project a wealth of new information to work through. This week, I was working on sorting out the children from that list, organizing them by age, and noting anomalies or interesting bits of information to investigate. As I was working with the data, I noticed one entry had a young child born in Kinderhook, NJ. The Reverend Ludlow’s mother and sister as well as many of his friends lived there, so I stopped to read the rest of the entry. And it was with shock that I discovered that the entry was for one Ann Gertrude Frey, born in Kinderhook, NJ, living on Vandam Street when she died from convulsions at the age of 11 months and 7 days. Ann Frey, or Anna Frey, relative of the Reverend Ludlow, and the subject of the poem, was buried at the Spring Street Presbyterian Church. It was something that makes sense, of course, but considering she was related to him through his sister’s marriage and that that portion of the family was from New Jersey, I had never considered the possibility that she was buried at the church. And, even more stunning than the realization that she was buried at the church, was the second realization I had looking at that burial entry: I had likely held her remains in my hands. I had examined every child’s bone that had come out of the burial vaults, and if her remains were among those that had been preserved, then I had handled it.

This discovery moved me deeply. I got choked up when I realized what this all meant. The little girl in the poem had been a symbol for me. I knew she had been a real child, but I had no information about her specifically. But with this new information, she suddenly was very real—she has a middle name, an address, a cause of death, and a body that I likely touched. Bioarchaeology is many things: it is science, it is history, it is storytelling. But it is also a type of remembering, an erasing of silences created by the passing of time. Over the 186 years since Anna Frey’s body was buried, her memory had disappeared. No one who knew her during her brief life was still alive, and no descendants of her family’s lineage have yet to come forward. And so the only memory of her was a hand-written, grief-stricken poem in a box in a research library in Cooperstown, New York. But bioarchaeological projects like these allow us to remember people like Anna—to find again their stories, and share them. Every time now that I read this poem during a talk about this project, I can tell the audience to whom I am speaking a bit more about her life, where she lived, how she died. I can tell them that her skeleton was likely among those studied by us at Syracuse University and that I had likely held her remains in my hands. A whole new group of people can enter into remembering her, the little girl in the poem, Anna Frey.

This is not the first such discovery we have made working on this project, and it certainly will not be the last. As we continue to move forward combining the skeletal data and the archival records, we will have the opportunity to remember many more fascinating people, people who lived nearly 200 years ago, people whose remains we have studied and learned from. We are greatly moved and touched by each story, and we will continue to share these with you here. We hope you will continue to follow along.

–Meredith A.B. Ellis

Lines on the Death of a Child

Cease here longer to detain me.

Fondest Mother drown’d in love.

Now thy kind caresses pain me,

Morn advances–let me go.—

~~~~~

See you orient streak appearing!

Harbinger of endless day,!

Hark! a voice, the darkness choosing,

Calls my new born soul away.—

~~~~~

Lately lamented, a trembling stranger,

On the worlds wild boisterous flood,

Pierc’d with sorrows, tossed with danger,

Gladly I return to God.

~~~~~

Now my cries shall cease to grieve thee.

Now my trembling heart finds rest,

Kinder arms than thine receive me,

Softer pillow than thy breast.

~~~~~~

Weep not o’er these eyes that languish

Upward turn’d towards their home;

Raptured they’ll forget all anguish,

While they wait to see thee come.

~~~~~

These, my mother, pleasures centre—

Weeping, parting, care, or love,

Ne’er our Father’s house shall enter—

Morn advances – let me go.

~~~~~

As thr’o this calm, and holy dawning

Silent glides my parting breath,

To an everlasting morning~

Gently close my eyes in death.

~~~~~

Blessings endless, richest blessings,

Pour their streams upon thy heart

(Tho’ no language yet possessing)

Breathes my spirit ere we part.

And to leave thee sorrowing, rends me,

[End of document. Original at the New York State Historical Association Research Library at Cooperstown, New York, in the Frey Family Papers. Transcribed by Meredith A.B. Ellis and David and Elizabeth Pultz to look as close to the original as possible]